Stitch Fix’s engineering efforts are guided by the pragmatic question, “What problem are you trying to solve?” We want to encourage experimentation and innovation within the constraints of our significant investments in our existing tech stack by iterating, improving, and integrating new tools and techniques. Our core languages and platforms are robust and well-supported both internally and externally, leaving plenty of room for creative and effective adaptation to our evolving business needs. But as new needs arise and new technologies emerge, we needed to consider how we can innovate in a responsible way.

A successful engineering culture encourages autonomy and problem-solving. But as we explore the use of different tools that may have value to our organization, we realized that we needed a clear process for ensuring that we stay current with the industry, make good decisions, and understand the impact of adopting new technologies.

Our Responsible Innovation Framework breaks this down into three primary activities:

- Evaluating the need and potential of a new technology,

- Testing the technology through responsible experimentation, and

- Consistently following a scope-based decision-making matrix for the change that we want to make.

Evaluating the Need and Potential for New Technologies

We consider exploring alternatives to our typical toolset when we encounter significant friction or come across a new technology or approach that may serve us better in the long term. The level of urgency for finding an alternative technology solution is determined by weighing the relative costs of doing nothing, waiting for an opportune time to explore and adopt something new, or making the necessary investment in the near term to better solve the specific problem we are facing.

Understanding the Problem Space

We begin by clearly articulating the problem that we’re trying to solve, and evaluating how our current technologies can be leveraged to solve that problem. This involves asking the following questions:

- Why is this new problem a priority?

- What business needs or decisions make this problem relevant?

- Is the utility or flexibility of our current technologies lacking in response to this problem?

- Have we used our current technology to its full benefit?

- Did we adopt our current technology solution under significantly different constraints or operating conditions?

- How costly would it be to apply our current technology versus adoption a new technology to solve the problem?

Answering these questions often involves discussions with our teammates to get agreement that the problem warrants attention, and that we have a good idea of how much of a priority the problem really is.

Strengthening Efforts vs Growth-Focused Efforts

Considering the answers to these questions, we move on to determining a general approach to meeting our technology need. The decision comes down to committing to a strengthening effort or a growth-focused effort.

A strengthening effort requires a careful analysis of the potential of our current tools to solve the problem and finding ways to adapt them to meet the new need. This may involve some degree of re-engineering, including process changes or extending the existing functionality of tools that we have already built.

A growth-focused effort requires evaluation of new potential options, considering the adoption costs and the overall benefit of each alternative carefully weighed against each other.

Examining Alternatives

If it is determined that our current tools are not well-suited to the emerging problem, and that a growth-focused effort is the appropriate way forward, we move on to evaluating alternative technologies that have the potential to solve it and choose the option that delivers maximum value for minimal effort.

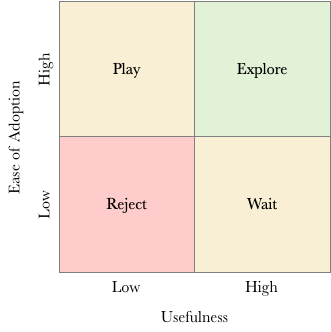

For this, we can turn to a technology adoption model that combines an assessment of the ease of adoption and the utility of a new technology:

Ease of adoption encompasses a number of considerations:

- Does the new technology enhance and fit well with our existing processes?

- Will it be easy for our existing staff to learn to use effectively?

- Is there good documentation and prior art that we can learn from?

- Is it flexible in comparison to our existing tools?

- Does the technology have a strong security story?

- Have we considered the overall cost to other teams that need to support the new technology?

Usefulness can be determined with this series of questions:

- Does the new technology enhance the performance of our teams?

- Does it positively impact the performance, stability, and reliability of our application infrastructure?

- Is it well-maintained, with an active user base and readily available support resources?

- Does it solve the problem more effectively than our current toolset?

This matrix guides our decision-making process. Technologies that are difficult to adopt and provide limited utility can be rejected outright. Easy to adopt solutions that provide limited value are not likely to be adopted but still may be worth exploring through ‘play’ (e.g. reading documentation and making simple proofs of concept), as they can create learning opportunities and help us gain a new perspective on the problem space. Technologies that provide utility but are difficult to adopt fall into the wait category; they may be candidates for future adoption, once the technology matures to the point that tooling and training exists to make onboarding easier. And solutions that are easy to adopt and accommodate a wide range of use cases are the most appropriate to explore, and can move on to the next phase: experimentation.

Responsible Experimentation

In our daily work we are often faced with novel situations to which existing patterns of solutions don’t always perfectly apply. As creative professionals, we need to strike a balance between consistency and standardization, and creative problem-solving. We operate according to our shared values of trust and being motivated by a challenge, and as engineers we feel empowered to explore solutions from a practical, pragmatic, and customer-centered perspective.

To inform and guide the evolution of our solutions within an environment of pragmatic innovation and creativity, we sometimes need to experiment with new ways of doing things. So how do we safely experiment?

Characteristics of a Responsible Exploratory Experiment

How we approach exploring a new technology has a huge bearing on its likelihood of being adopted as a standard. So what makes a safe and responsible technology experiment?

A responsible experiment has:

- A clearly defined problem statement;

- A well-understood and well-documented use case;

- Minimal impact on our own and other engineering teams’ priorities;

- Minimal impact on other applications and systems;

- Well-defined boundaries;

- Buy-in from the team and its manager;

- Success and failure criteria against which it can be measured;

- Clear and concise documentation;

- Evidence of thinking about alternatives and tradeoffs;

- Analysis of the impact on operations, security, scalability, and observability;

- A constrained time and cost; and

- The ability to be undone or rolled back with a minimum of cost and effort; the artifacts of such an experiment are likely to be short-lived and replaced with more maintainable and production-ready code.

Every technology decision that we make has ripple effects beyond the code in which it manifests. New frameworks have an operational cost and associated security concerns. Third-party solutions must be analyzed for their long-term sustainability and likelihood of being properly updated and maintained. Esoteric or highly specialized technologies may have an associated learning curve (and a limited number of engineers capable of maintaining and extending the solution, which impacts hiring and staffing.) In short, we must recognize that decisions made by an individual developer or small group of developers may have an impact beyond that team’s domain.

After carefully experimenting with a new technology, and seeing the benefits of its adoption, it’s time to move into the decision-making phase.

Responsible Decision-Making

Our engineering culture is designed to empower our engineers and grant individuals and teams great latitude in their approach to creating technology solutions to meet our business needs. But understanding that some of these decisions have a wider impact, we must be careful and thoughtful about their widespread adoption.

We need to strike a balance between our desire to be consensus-driven and our need to be thoughtful, pragmatic, and deliberate about the decisions we make. We must rely on a clear and efficient decision-making process that both rewards creativity and innovation, and draws on the hard-won experience and insight of senior engineers and managers.

Decision-Making Framework

Who is responsible for making technology decisions? It comes down to a question scope: asking ourselves, who is impacted by this decision? This is where an emphasis on partnership becomes critical.

Team Scope

When the impact is limited to a single application or team, individual developers are trusted to make the right decisions about their approach to solving a problem.

As an example, a developer may explore the use of an architectural pattern that would be relevant to solving the problem at hand, even if its application is novel in the context of the team’s prior work.

In cases like these, we discuss our idea with our teammates to ensure that our change is acceptable and will be understood and documented well enough that it can be effectively supported by our team.

-

Responsible: An individual engineer (or small group of engineers) leads the effort. They are doing the work on the implementation and making sure that it adheres to the guidelines of a responsible experiment.

-

Accountable: The team’s manager, in collaboration with senior engineers, is ultimately accountable and has the power to decide if the experiment will be put into production.

-

Consulted: The entire team should be kept informed as to the setup, execution, and evaluation of the experiment. Feedback may be collected by reaching out to members of the team and through code reviews.

-

Informed: The responsible engineer should take responsibility for socializing the experiment to the broader engineering organization in case it applies to problems that other teams are facing.

Cross-Team Scope

When a change we want to make impacts one or more other teams or applications, we document our proposed solution and share that documentation with owners of those applications, including managers and representative engineers from those teams.

An example of cross-team scope is the extraction and integration of a new service that has potential use by multiple teams. We collaborate and iterate until we have agreed on an approach that meets the needs of all of the people who are affected by the decision.

-

Responsible: A small group of engineers representing multiple teams lead the experiment. The experiment should be well-documented, and the documentation should be thorough enough for anyone to read and understand what is being tested, why it is being tested, and what the impact of the technology will be if it is successfully adopted.

-

Accountable: The managers and senior engineers of the affected teams have the ultimate decision-making authority.

-

Consulted: Senior engineers from all affected teams should be consulted in the design, execution, and evaluation of the experiment. Note that the new pattern, tool, or technology may have unexpected impact on infrastructure and security concerns, so the people responsible for these areas should be consulted as well. The team leading the experiment should also solicit input from other engineers who have an interest in the topic, and regularly report back to them on the status of the experiment.

-

Informed: The engineers leading the experiment have the responsibility to socialize it to the broader engineering organization.

Engineering-Wide Scope

When a change impacts multiple teams, requires operational support in terms of infrastructure or security, significantly changes our approach to solving a certain set of problems, is costly in terms of time, effort, or price, or has broad business implications, we need to draw on a larger group to leverage their relevant experience and insight into the problem and proposed solution.

For example, if we were interested in adopting a new testing framework or adopting GraphQL API interfaces, this effort would only be successful by securing buy-in from our most senior engineers and managers well before we explore integrating these technologies.

-

Responsible: The working group of engineers leading the experiment.

-

Accountable: One or more senior engineers and managers (and potentially product partners or even executives, in the case of a large-scale adoption proposal) are ultimately accountable and have the authority over the final decision to adopt or not adopt the new tool, framework, or language.

-

Consulted: The experiment team should be in regular communication with senior engineering staff.

-

Informed: The team should take responsibility for socializing the experiment in the broader engineering organization. They should schedule presentations and Q&A sessions to fully inform other engineers and managers about the change and how it will impact them.

Striking a Balance

To preserve a culture of broad participation in decision-making, we must do our best to communicate clearly about the problems we face and how we can solve those problems in new ways. Partnering with our peers improves our chances of success, not only during the experiment but also as we move into the adoption phase for a new tool or technology.

We must also recognize the limits of driving toward consensus. Ultimately, we rely on our managers, senior engineers, architects, or other project sponsors to evaluate and approve significant changes to our tools, processes, patterns, and infrastructure. We trust that the decisions that they make will be informed by the results of our responsible research and experiments, the comprehensive documentation we have prepared, and the input and buy-in we have secured from across the engineering organization.

Regardless of the scope of the change we want to introduce, if we have done our jobs with due diligence, we can trust that the accountable individuals are well-equipped and empowered to make an informed decision that we can all believe in and support moving forward.

Final Thoughts

We understand that changes to our tools (and the resulting infrastructure implications) can have significant impact outside of our own individual or team domains. In order to stay most focused on delivering value to our clients, rather than getting lost in the details of complex technical problems, we want to keep the number of different technologies we use to a manageable and effective minimum.

Success is predicated on being deliberate and methodical in the way that we experiment with new technologies and how we make decisions about which technologies and techniques we will adopt.

We want to preserve the balance between pragmatism, creativity, and autonomy. In order to do this, we need to be deliberate about how we explore, experiment with, and choose to adopt new tools and technologies. We have to balance our attraction to the new and novel with realism and deliberation. And we need to trust our technical leaders to make informed decisions.

In short, we need to recognize that real and sustainable innovation is a team effort.